Suspension of disbelief in fiction is tricky. What logic or laws of reality is one willing to put aside for the sake of story? I personally find myself become less and less tolerant of stories that abuse such rules without a good reason to do so.

Sometimes genre comes with its own exceptions. How often do we, in reading or viewing, encounter a science fiction story in which scientists explain to one another a fact that doesn’t need explaining. The information is essential for the reader or viewer, but it’s method of transmission contradicts story and character logic. This happens all the time. Two soldiers discuss a plan they already would have known. A sorcerous talks to herself in detail about a spell she has used before. Typically, if we notice the flaw, the story has failed to cast its own spell on us. Hasty or lazy writing is to blame.

The other day, I watched a documentary on the first Ghost Busters film. Although even comedy must follow its own story logic, we make a special exception for absurdism. A colossal Stay Puft Marshmallow Man trudging through New York City makes perfect sense, as did the DeLorean time machine in Back to the Future. Perhaps the 1980s was the heyday for making the silliest story developments seem plausible.

I’m still thinking through ideas for my story for Cold Hard Type. Some ideas will make the cut. Others won’t. One scene I drafted features a moment in which the time traveler, who remained stuck in the past, finally confesses to his wife of many years that he is from a different time. He takes her to a hotel to reveal the truth. How can one imagine how such characters would behave and react? Imagine all of the emotions and thoughts she would experience. Imagine her questions. The idea is absurd, yet it must be depicted. I’m not sure how well the draft worked, but what I do know is that, every time I draft a scene, I find myself becoming more intimate with, and knowledgable about, my characters. They become more nuanced and real in my mind.

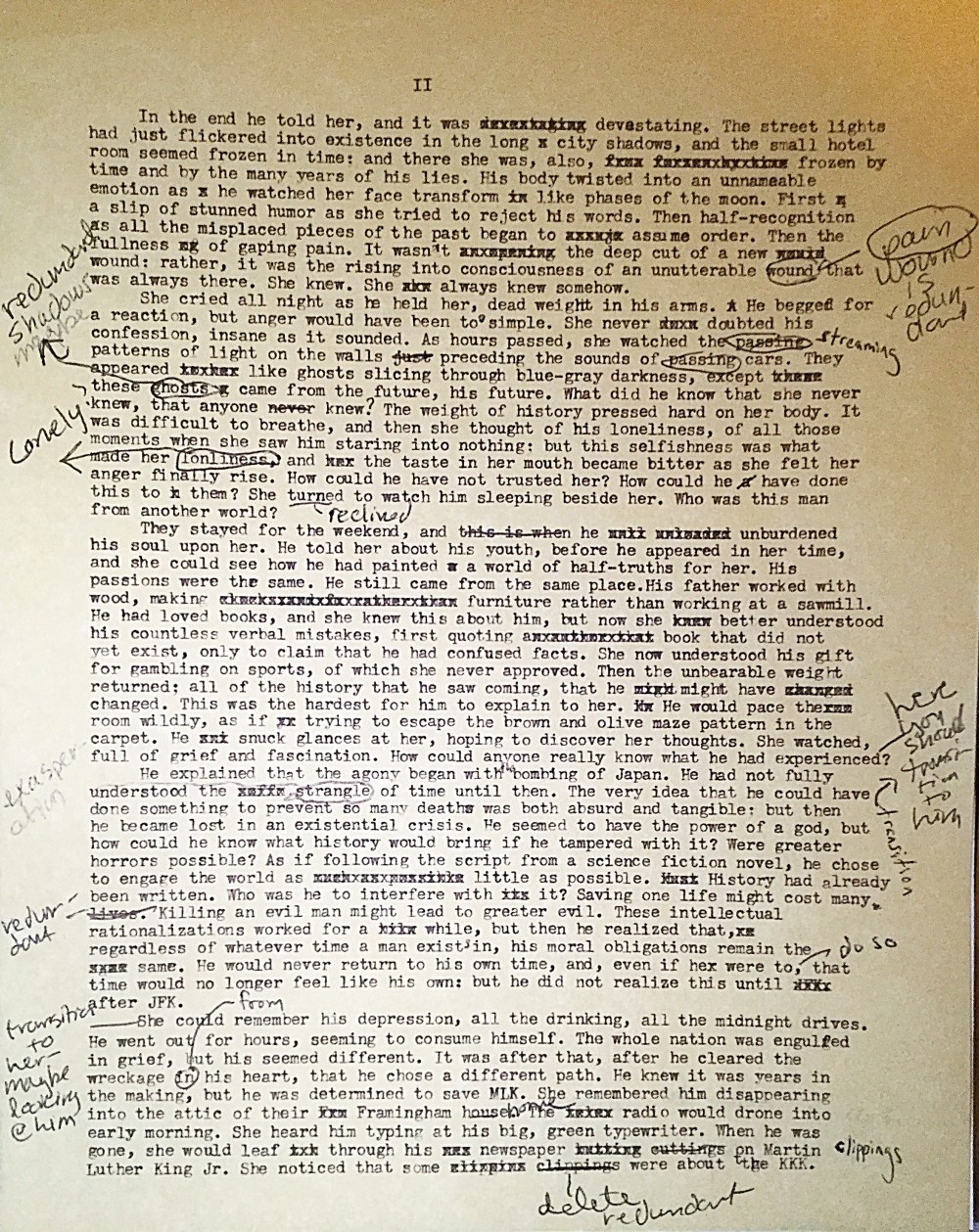

Here’s the first run through the incomplete scene, with some handwritten notes by myself and my girlfriend:

Another issue I’m mulling over is how to realistically capture Boston, specifically Roxbury, in the 1940s. I’ve been doing all kinds of research. What buildings were there? What didn’t exist yet? One lucky find was the Autobiography of Malcolm X. Guess who was there in the 1940s? He lived with his half-sister in Roxbury as he grew into early adulthood. This was before his imprisonment in Charleston, where he educated himself and converted to Islam. His descriptions of Roxbury are vivid, teeming with life and lifestyles. The next question is whether my protagonist will run into young Malcolm. He won’t run into Martin Luther King Jr, who later studied at Boston University. (Other tidbits that might come up: W.E.B. Du Bois acquired his PhD at Harvard in 1895. Crispus Attucks was killed outside the Old State House.)

———

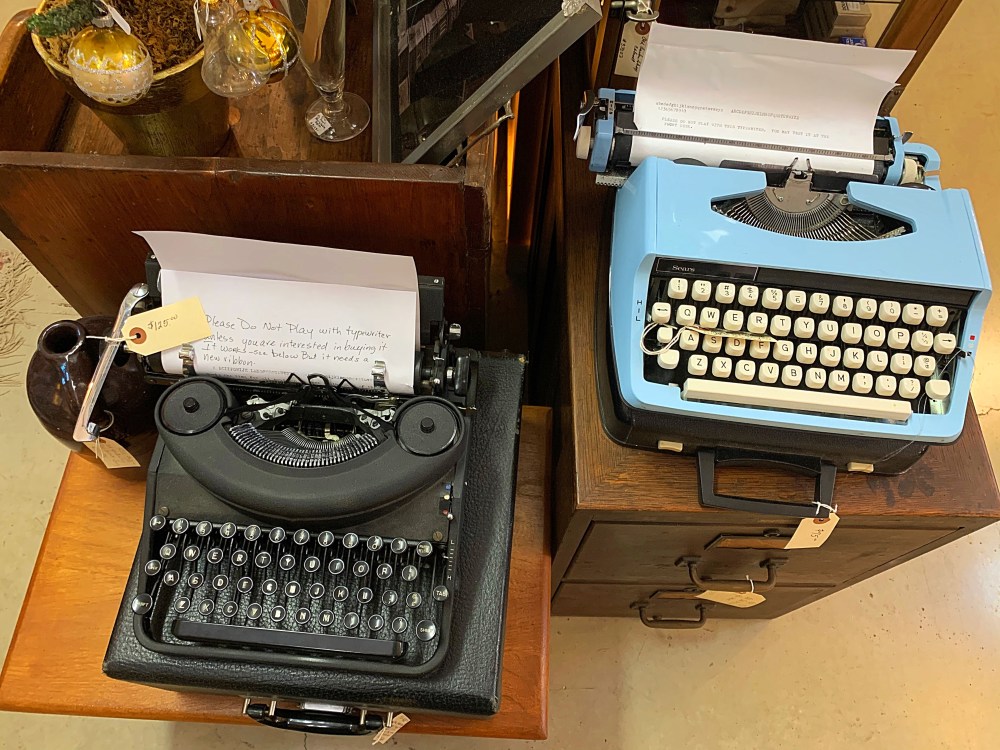

In other news, we went antiquing in Comfort yesterday. It’s a small town with a few good antique shops. My girlfriend found some good supplies for art. I had less success with typewriters.

The noiseless was tempting, but not at $125. The SC was in a large, exposed shed in a backyard. The antique store filled me with dread. Books and mechanical items were in the open air, decaying in the elements. Tacky objects were kept inside. I understand that value is subjective, but the store was set up like a Michaels or Hobby Lobby. There was no logic to the displays and history played second fiddle to “shabby -chic” crimes against humanity.

The problem of clumsily informing the audience is hardly limited to science fiction (where, in truth, I’ve rarely encountered it since I started reading with discrimination). Mike Myers winked at it in the first Austin Powers movie by naming Michael York’s character “Basil Exposition.”

The idea of a time traveler encountering a young Malcolm is interesting. I’m sure you won’t make the mistake–as common as clumsy exposition–of attributing to an adolescent historical figure a character that only matured with time. Young Malcolm was a drug dealer who went by “Detroit Red.” How would you include such a figure without either demonizing him or glossing over his flaws?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Too true. I don’t think there will be an extended encounter. In fact, my traveler might not put two and two together. A marginal character might call out Malcom’s nickname, and the reader may or may not catch the reference. One of the most absorbing, and pretty convenient, elements to a realistic portrayal of time travel is that the traveler would not remember precise facts about the past. If you were sucked into the past, what reliable historical knowledge would you recall? Would you remember the precise day and hour of specific moments—like an assassination? My protagonist will have a general knowledge about some events. He will know enough to bet against the Red Sox in a World Series.

Malcom X’s autobiography is an honest account, by the way.

LikeLiked by 1 person